Anonymously published document. Full document here. Originally spotted on Revolutionary Horizon‘s facebook page.

We are republishing a collection of excerpts from a larger piece composed of interviews with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated folks from Texas, Illinois, and Florida. The original document uses interviews and case studies with prisoners, guards, and historical analysis to demonstrate how prisons are extensions of the plantation system and mirror pre-1865 slave codes. We’ve highlighted passages that reflect the experiences and conditions of inmates in Texas prisons. We hope this will give students and other non-incarcerated folks a better idea of the conditions and struggles of prisoners, and expose students to some of the worlds that we are isolated from. In particular, students should recognize the complicity of their own schools in this system. UT’s Investment Management Corporation indirectly invests in two of the largest private prison companies, Corrections Corporation of America and the GEO group [1]. The prison has long been the hidden underside of the University. While the University produces new citizens & professionals, the prison strips away citizenship and produces captivity. We hope the following excerpts will inspire greater awareness and energy for anti-prison organizing.

Mental & Physical Deprivation

The most blatant form of state-sponsored cruel and unusual punishment is welfare checks. Both D in Texas and R in Florida have reported welfare checks. Every 3 hours at night, guards will come by and knock their keys on inmates’ steel doors, hit the bars of their cell, and shine flashlights in the prisoners’ faces. It is required that the prisoner shows some kind of movement before the guard moves on. An average REM cycle needed for rest is 3 hours, the exact time when a guard will come by making noise all throughout your cell block. R explains “having to sit up every couple hours destroys you… you can’t sleep anymore… you’re just laying down all day.” L corroborates this from his experiences at Menard, sharing “you never get any straight through sleep.” David formally writes a grievance about his 29 days in Stiles Unit’s 12 building, “which at this time is used for segregation, overflow, and high security housing.” He writes in a grievance, “I did not get 1 full nights sleep in the 29 days I was in building 12 because of the guards slamming metal doors loudly throughout the night and shining there flashlights into our faces while we are sleeping just so we wake up and know we are alive. It’s called a (wellfare check.) But what it is, is a form of cruel and unusual punishment. Most nights I never got more than an hour or two of sleep without being woken up by slamming doors or lights in my eyes.” I have observed the results of this sleep deprivation first hand. While waiting in the visitation room for D, I studied every inmate. Almost all of them had dark bags under their eyes, so did D. This program of is also used in Immigrant Detention Centers, although guards will come by every 15 minutes due to some horrible Child welfare and services law (Chicago Human Rights Journal)… S told me that Cook County operated welfare checks 3 or 4 times altogether in the morning, day, and night.

Limited possessions

The state ensures that inmates can’t try to mitigate these horrendous conditions without paying a heavy price. Basic necessities come at an absurd price. One may buy a limited amount of supplies at commissary if you have a family or friend putting money on your account. So, if you don’t have commissary money, you have no fan no radio no food no nothing besides the meager amount the state gives you. But even if you have some money to go to commissary, it doesn’t happen everyday. For instance, David explains that in Texas at a TDCJ Unit he visits “every 2 weeks and ha[s] a 90.00 dollar limit” but during lock down is allowed once a month. D told me that unless you can purchase a lamp at commissary, you will not be able “to read at night when the buzzing light goes out.” B, who served a sentence for retail theft at NRC Stateville, explained that inmates get “no paper, no writing letters…” you “can get your mail but it’s a whole different process to get it in there and it takes five times longer to get your mail in prison than in the outside world because it has to be given so many kinds of checks.” There are many restrictions about people from the outside world sending material that is not straight from a recognized company. Many prisons including in Texas require that books be sent from a bookstore or publisher only. David shares that at Stiles Unit, the guards “check the book when it comes into the mail room against a list of approved or unapproved books.”

The state provides tiny rations of highly limited supplies for its poorer “indigent” offenders. Indigent supplies provided by the state do not cover many of the basic necessities. Indigent refers to a prisoner who enters prison with no money on their “books” or financial account. D writes in a grievance: “Another serious issue is, Indigent supplies. An inmate here at Stiles Unit who does not have funds in there commissary account are give the following indigent supplies, five 1 inch wide and 1 inch long bars of green soap, 1 razor to shave with, 1 roll of toilet paper. Then once a month they are given a 3 ounce tube of toothpaste which has to last 1 full month. Indigent inmates are not given the following items, deoderent, shampoo, dental floss, Q-tips, body lotion and anti bacteria soap. Once again cruel and unusual punishment applies, Indigent inmates are forced to live without basic health care items and suffer in the hot summers with very bad body odors because of lack of deoderent or body lotion.”

David has commented on how inmate’s dental and physical hygiene is horribly poor within prison and worsens throughout the sentence. Furthermore, “if you have no money on your account you are allowed to send out only 5 letters a month. They provide the paper pen and envelope. If you ever get money sent to your books they take the money that you used on indigent mail.” I watched a Ratface Film called 12 Scenes of Slavery and learned you cannot send, for example, cassette tapes with screws or CD because they “could be used as weapons.” They allow the shipment of other things that may be turned into weapons. Obviously safety isn’t the consideration but rather the deliberate refusal of human pleasure to prisoners. L says he received “a piece of crap toothpaste, two pairs of underwear, two pairs of socks, 2 tshirts, and 1 Bob Barker deodorant. In Cook county jail, you are given 1 or 2 sheets, often thinned out and ratty, one toothbrush, toothpaste, a towel and soap.”

S told me that in Cook County he was given “shower shoes, a uniform, soap, and deoderent.” S shares that “most people don’t get commissary because they got booked without no money or its hard to get your family to send. Guys in there fighing over food because they haven’t eaten good in months…. I almost fought over food someone tried to take my stuff…” He explains that in Cook County division everyone kept his box of items under the bed. When he returned half his food was gone- “The guards don’t care ‘Its jail’ that’s what they’re gonna tell you.” Personal belongings are often exhorted by others or confiscated and mishandled. David explained to me that when you are transferred from one cell to another all your personal items are taken away in a bag. Guards handle, process, and redistribute the bags to offenders but this can take weeks or months.

David tells me at TDCJ Unit prisoners are given 3 pairs of socks and 3 pairs of boxers that they can exchange every 3 days for a clean set. D calls prison a “place that is defined by such things as… go[ing] to bed hungry or wash[ing] my ass with green lye soap…. The prison took out there blood money for my medical visits and the indigent materials I’ve been useing to write you. D is given a roll of toilet paper that must last a week. D is refused pay while working at the cafeteria of his supermax prison in Beaumont. Even if he made the average wage of most prisoners, some 6-40 cents a day, he would struggle to afford the 50 cent toilet paper sold through commissary. Thus, if an inmate wants enough toilet paper to wipe their ass with each time, they have to depend on friends or family on the outside to afford them. This relegates inmates to an extreme position of dependency.

Inmates’ limited access to items is a clear parallel to slaves’ inability to own property. Slave codes commonly held that slaves could not own anything of their own right, nor could they purchase, sell, or trade goods. Within jails and prisons there is a very limited amount of items that are not considered contraband. For instance, within solitary confinement of Pontiac Correctional Facility in Illinois, colored pencils are considered contraband. Technically, inmates are not allowed to exchange or trade their items for others. D tells me that in Stiles Unit most guards are decent enough to momentarily turn a blind eye to the trade of books. However, D said that within Stiles Unit if you are caught giving out or exchanging coffee or stamps, they will be confiscated. David writes, “but things exchanged are things humans, especially in these torturous conditions, NEED to operate!!… a friend of mine passed me a few shots of coffie so I’am enjoying a cup as I write this.” The people in David’s building go to commissary after many others do, so by the time he arrives there’s no more coffee or peanut butter.

Dehumanizing Prison Punishment

S says “the majority of the time if you put in a grievance form when they come ask you ‘what did you do for the guard to react, did you disrespect the guard?’ If you say ‘I cussed,’ they’re gonna say that’s the reason why. You have to be bare right innocent to maybe get something in your favor off the grievance form. If you said anything wrong, it’s not gonna go in your favor.” For instance, once S approached the guard in his division to ask for his court date. Guards are supposed to look that information up and inform inmates, yet this guard kept saying to get away from the glass window. So, S and the guard argue. The superintendent resolved the conflict not through chastising the guard for his laziness but by simply moving S away from the friends he had made in his division into another one. Inmates are left as helpless insects in this web of socially and legally backed abuse. Inmates’ only avenue for voicing their distress is through a broken grievance system. S shares, “you can request a grievance form if you’re being mistreated but the thing about the grievance form is you’re probably not gonna get a response for 2 to 3 months later from them. So sometimes its like really what’s the whole point… It takes sometimes weeks, months, it depends.” David offers some more context to the greivance process in Texas Department of Criminal Justice prisons: “They have 30 days to answer a grievance but they can also get 2 15 day extentions. So they can drag it out for 2 months if they want.”

So, the system is such that it is nearly impossible for an inmate to voice their fair opposition to the abuse they face. Furthermore, political organization and radical activism within prison is a crime punishable by solitary confinement. At Folsom Prison, a man was thrown into solitary confinement for hunger fasting. I spoke to David about this strike, and D said, “a lot of the points hit home for us here in Texas such as (end cruelty, noise and sleep deprivation of welfar checks)…” He goes on to further list his grievances: “Also: Provide meaninful education, self help courses and rehabilitative programs. No such thing. It’s just in name only. God damn Sloan. I wish I could get it out there what’s really going on in here. From the abusive guards the segregation unit to the swarms of fucking cockroaches in our cells. We don’t dare go on hunger strikes or buck the system becaus they will bury us in seg and you wouldn’t see us for years.” I asked David whether there are consequences for unionization, to which he replied, “Oh God yes. If admin were to ever get wind of that heads would roll. And if someone ever tried to organize a work strike, hunger strike etc—he would dissapear into the bowels of seg in some undisclosed part of Texas.”

When D first mentioned his attempt to file a grievance with other inmates, he stressed that they were following the legal processes directly. He wrote: “We are thinking about filing grivences on the mental verbal and phyisacal abuse we are subject to everyday. But we have to be carefull how we do it because we are sure to be retaliated on. We have to leave a clean paper trail so they have to be carefull not to fuck us over.“ Here David refers to the prison’s tendency to respond to social justice activists with unit transfer and solitary confinement. A felon named “M” from Chicago confirms you do indeed get in trouble for filing a self-drafted petition. Often, the punishment is longer periods of cell time during the day.

An inmate’s chance of state retaliation is high, even if demanding change in an officially recognized way. For instance, a new development has happened since I first wrote this section. David and his friends put together a list of the cruel and unusual punishment they face in 12 building used for solitary confinement. Their intention was to send it to the ACA but instead David sent it to me. For their activism, David and his friends were sent to seg overflow in 12 building (solitary confinement). Not a coincidence. All these men did was utilize their right to free speech and the state responds by placing them in a cell for 23 hours a day. Jails and prisons offer harsh, heartless punishments for even more victimless crimes. For instance, 2 weeks before B was set to be released from prison in Illinois for retail theft, he was set with a new charge. B was using the bathroom while someone was snorting a psychotropic drug traded in prison. For not reporting drug use to the guards, B was given another charge facing 4 to 15 years. He was then sent to solitary confinement in a medium-maximum prison called Statesville in southern Illinois.

Slavery: Forced and Unpaid Labor

Saying prison labor is a form of enslavement is not an exaggeration or some simile but a reality backed by the constitution. The 13th Amendment abolished the enslavement of individuals unless they are committed of a crime. Again, the 13th Amendment, partially abolishing slavery, does not apply to people we have labeled convicts in our racist courts. Slavery, unpaid slave labor, is currently legally backed by the constitution of the United States. Prison labor is an extremely exploitive form of slavery. In many states including Texas, Arkansas, and Georgia, inmates are forced to work on and off site for no pay. In other states, it’s a handful of cents an hour.

And yes, it is mandated to any inmate deemed able-bodied and it is punishable by solitary confinement, loss of parole, and more. R explains that in Florida, “You have to work for the prison. If you don’t work they’ll put you in solitary confinement.” In order to resist the torture of solitary confinement, R slaved away in the scorching hot kitchen and laundry room of the prison. He cooked and washed and folded clothes for no pay. D explains the forced labor he encountered when he first entered Stiles Unit in Texas: “I was given a job in the kitchen scrubbing pots and pans. I was told by the kitchen seargent that if I did not report to work I would be written up and given punishment. This would hurt my chances of getting paroled. The conditions I worked under were brutal, over 100 degrees, I was forced to wear thick pants and shirt and rubber apron. This is just one of the many hard jobs that we inmates are forced to do with no pay.”

By not working, inmates lose“good time” points and thus worsen their chances of parole. S explains, “They call it good time- if you have no fights no nothing they give you good time credit that means they might take some days or years off your case. They might let the judge know they’ve been good.” Because of his good time credit, Shawn received 61 days off his sentence by a judge that deemed S “not a threat to society.” So, the alternative to not working is looking bad for the parole board or judge and staying locked up in jail or prison for even longer. However, for the record many other inmates have told me these “good time points” are often all talk and don’t stack up to much.

In another letter, D summarizes the labor system perfectly: “First of all it really is slave labor. When you come into any Texas Prison you are given a job. If you refuse to work you get a write up and that jeperdises your chance of parole. If you continue to refuse to work the write ups add up and your custody level goes up and you get locked down. They have a status called G-4 and that’s where they put you for refusing to work. You stay there for min of 6 monthes, but usually 12 monthes. Here are the workers who suffer the most: kitchen workers mostly pots and pans washers, scullery workers “dishes etc” it gets over 100 degrees in those areas and all they have is 1 fan for the whole area. Those workers are in that heat 6 to 8 hours everyday in the summer. Then they have ‘Hoe Squad’ that’s when you are marched out to the fields to work under the guards on horseback with guns. Those inmates work there asses off (again for no pay.) Then you have the laundry workers who wash dirty nasty clothes, in a hot ass room all day. I could go on and on Sloan but you get the drift it’s slave labor.”

Separation from family and friends

In my experience, TX friends&family calling program to prisons uses CenturyLink and Securus technologies. I know that one of these companies is charging me about 26 cents a minute- that’s $15.60 an hour- to talk on the phone. While I am privileged enough to afford this, barely, this calling rate is more than two times the minimum wage in Texas of $7.25 an hour. The majority of people affected by the prison industrial complex are low income, meaning many family and friends cannot afford these rates and simply have to deal with not communicating with someone they care about. According to Prison Policy Initiative, the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) capped the cost of interstate calls from prisons at $10/ half hour. The prison industrial complex operates off exploitation of the poor and working class. You can only talk on the phone for 20 minute intervals before it cuts you off and there aren’t enough phones for everyone in the dayroom to use. The other option is to write via snailmail for the price of a stamp or use a private company like Jpay to send an email, 47 cents a page or a photo. Indigent inmates are given restrictions on how much they can write; in Texas Stiles Unit it’s 5 letters a month.

Furthermore, jails and prisons will often unfairly punish an inmate by taking away their ability to use the phone. The following is taken from the TDCJ Offender Telephone System (OTS) Assistance Request Form: “Phone accounts will automatically be suspended for 90 days on conviction of a major disciplinary. Offenders in transient status will also be suspended. No calls can be made until your status has been cleared. OTS representatives are not able to answer questions about offender suspensions.” Prisons and guards call phone calls “privileges” rather than a basic right to connection with friends, families, attorneys, activists, etc. Prisons will separate inmates from their families and support networks as a form of punishment, and that is horribly cruel. Inmates cannot even legally communicate with other inmates in the prison through mail, so they are made to effectively be as alone as possible.

Poor medical attention

A Marshall Project article by Elizabeth Eldridge called “When a mental health Emergency Lands You in Jail” states that “Across the county, and especially in rural areas, people in the middle of a mental health crisis are locked in a cell when a hospital bed isn’t immediately available. The patients are transported from the ER like inmates, handcuffed in the back of police vehicles. Laws in five states- New Mexico, North and South Dakota, Texas and – explicitly say that correctional facilities may be used for what is called a ‘mental health hold.’ Even in states without such laws, the practice happens regularly. A guard named J told me its commonplace in Texas to place a suicidal inmate in solitary. Well, according to research by the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), “the risk for suicide, self-harm and worsening symptoms increases the longer a person is behind bars.” Treatment is for depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, which plagues places of incarceration, is nonexistent.

Support!

This pro-inmate legislation … add abolition to your political agenda

TX SB485 : Introduced by Houston Senator Borris Miles, this legislation would create an independent oversight ombudsman to investigate TDCJ in all its human rights violations

Email tdcj@tdcj.texas.gov ombudsman@tdcj.texas.gov exec.director@tdcj.state.tx.us oscar.mendoza@tdcj.texas.gov in support of this decision

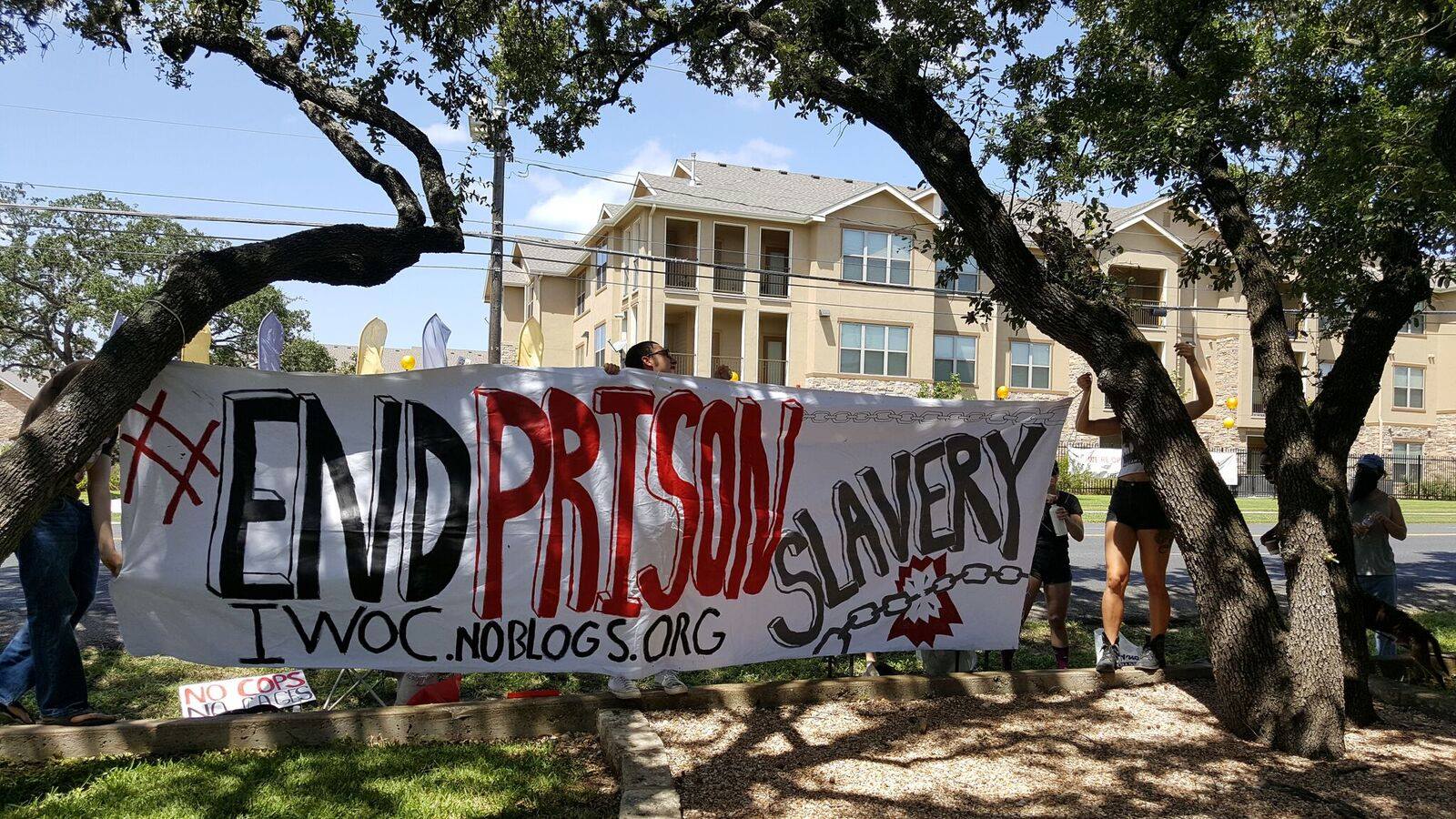

Editor’s note: Also be sure to follow groups like the Austin Anarchist Black Cross & the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee to find out more about local prisoner struggles.

Interested in contributing to a media project that aims to let the marginalized tell their own stories? Got interesting content and want a platform to publish? Submit your content to us at austinautonomedia@autistici.org! We take all kinds of stuff–reviews, art, poems, analysis, news, reportbacks from events, and more–as long as they don’t violate our principles